The Look of Mourning: Loss and devastation in the eyes of refugees

Photographer & FARA volunteer, Catalina Urse's powerful first hand testimony from the Ukraine/Romania border

I entered the refugee centre, trying not to make any noise. I had imagined how tired the people must get, travelling the long road from Ukraine to Romania.

But as I opened the door, I was greeted by cheerful voices and the sound of children’s laughter. A small, colourful, unicorn of about 3 years old, with blond hair, a tail and the bluest eyes jumped in front of me. Although I could not understand a word, I could tell the unicorn was singing a cheerful song. The unicorn is, of course, a child – a little girl, playing dress up in a unicorn costume.

The child was followed by her grandmother – a beautiful, smiling, delicate lady. Yet her smile was in contrast to the look of trembling sadness, sadness that I will come to see again and again in the eyes of all refugees. In fact, ‘sadness’ is too small and insignificant a word to describe exactly what their eyes say.

It is bitterness. It is agony. It is MOURNING.

A relentless mourning, of grief, that the refugees feel for the loss of their lives as they knew it. For a country now destroyed and left behind under the smoke. Of the cities erased from the map, of the loved ones they have left behind (the Grandmother’s husband had stayed behind in Ukraine with her brother, as he could not travel). Of the loved ones now gone.

It is difficult for them to tell us the fear and the horrors they went through, even those who have come from the epicentre of the war.

It is not because they don’t want to tell their stories, but because the language barrier prevents them from verbally sharing their pain. But it is obvious, there is no need for words. The pain is there in their worried and weeping eyes, in the deep, dark circles underneath them. I still find the strength to smile, I do it for children. Most of the Refugees have left Ukraine for the children; it is the children who give them the strength to move on.

My thoughts flew for a moment to my own children, safe at home. I thought of a time when I didn’t let them play a game that seemed too violent, or let them see a movie that could affect them emotionally. How ridiculous it seems now, how absurd, how unjust. Here, these women have to protect their children from a real war, from tragedies and horrors that even the minds of adults cannot conceive.

How do you explain to the child that bombs are falling outside?

How do you explain that people are killed in the middle of the street, or while queuing to buy bread? That their grandfather was killed? That they don’t have a house because it was destroyed by bombing. That their father has to stay behind and defend the country, and that he cries because it might be the last time you see each other?

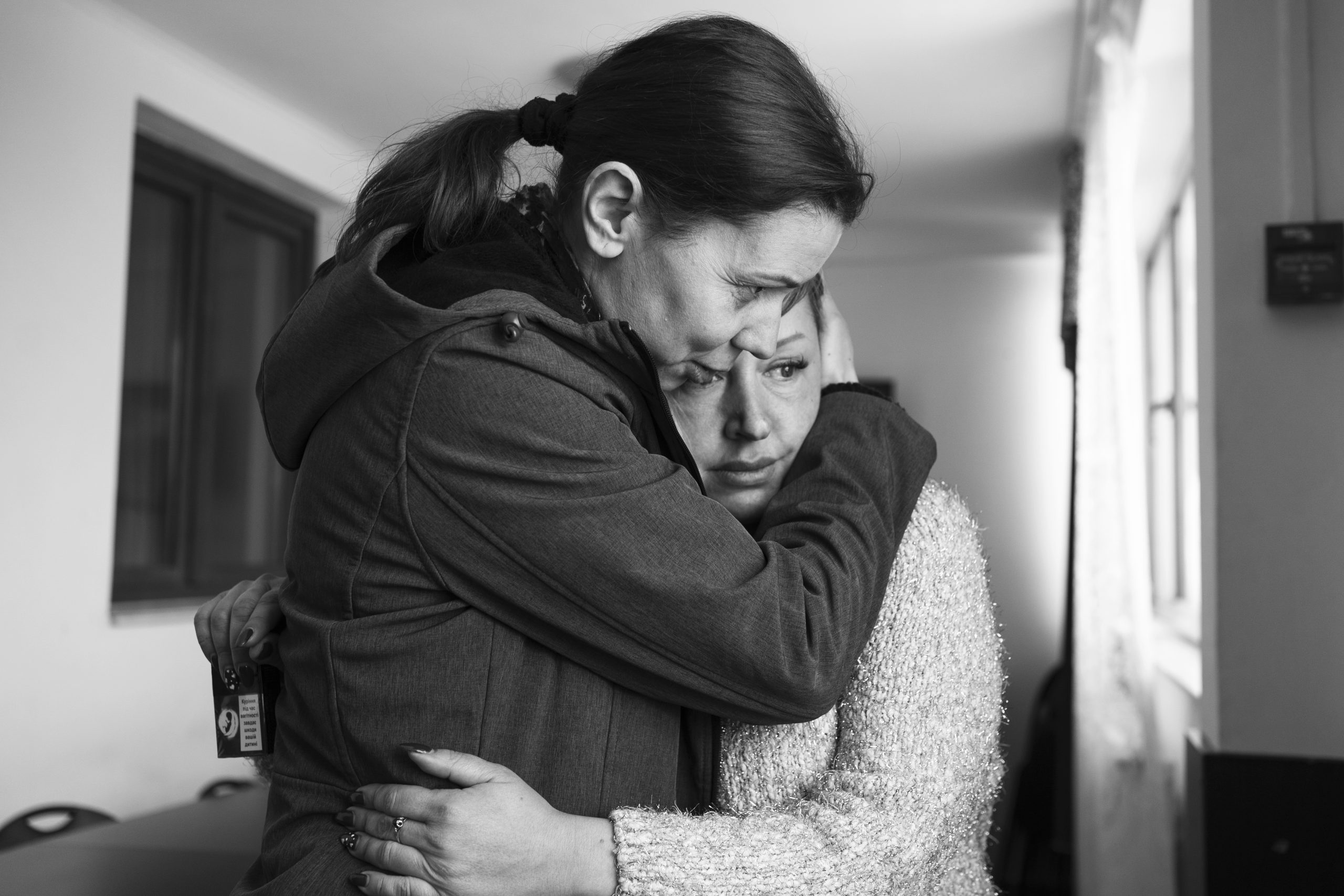

Raluca, the coordinator of the refugee centre, has become their trusted person. She is the one they know they can rely on, the one who offers them comfort and relief, even if she doesn’t know their language. Raluca has learned a few words in Ukrainian, and the little ones have learned a few words in English, otherwise she is saved by technology and a young refugee who knows a little more English.

The mother of the little unicorn is young and beautiful, as is her daughter and her own mother. Three generations of beautiful and strong women. The young mother is happy when she is around her daughter – she laughs and tickles the little one, while playing along with another girl of the same age, who is also a refugee. Upstairs in the centre there is a playground, and the children are excited to receive a new set of toys.

Meanwhile, Grandma goes out into the yard to smoke a cigarette. She leaves us smiling, but once she is outside and thinks that no one can see her, she begins to cry. She cries bitter tears that trickle down her cheeks, calmly and tirelessly.

I try to put myself in her place, to imagine being forced to leave my husband and my relatives at home. I try to imagine my home turning into a place of death, not a place of safety, and having to flee to a foreign country. A country where I do not know anyone, where I don’t know what will happen to me. I’m shaking. I would like to hug her and tell her that everything will be fine, but I’m not sure it will and I can’t hug her, because I’m just a stranger with a camera.

Raluca comes to me and tells me that the lady always cries, inconsolably, day and night. I see her put out her cigarette, wipe away her tears, and enter the house. Raluca does what I couldn’t do – she hugs the Grandmother tightly and strokes her face and hair. It’s an intimate, tender gesture, which speaks of how close she has become to them in the few weeks since they arrived at FARA. The lady’s eyes fill with tears again, but this time she manages to control them. Only the deep circles and swollen eyes still speak of the many nights spent in tears, and the deep fear she feels for her loved ones.

Mourning is worn, not just like clothes, it is worn by the eyes, deeply buried in the hardened features of suffering. And no smile in the world can hide it.

Cătălina Urse, Photographer and Volunteer

More about CatalinaI would like to hug her and tell her that everything will be fine, but I’m not sure and I can’t hug her, because I’m just a stranger with a camera.